What Is Listeria and How Can You Protect Yourself?

By: by Amino Science

By: by Amino Science

Listeriosis is a serious infection primarily contracted from food contaminated with the gram-positive bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The agency estimates that 1,600 people contract listeriosis each year and that 260 die. Fatal in one of five people, Listeria infection is the third leading cause of death from food poisoning in the United States, and the most vulnerable are pregnant women and their newborns, people aged 65 or older, and those with compromised immune systems.

While pregnant women have a 10 times greater risk of succumbing to L. monocytogenes, pregnant Hispanic women are 24 times more likely than other people to contract the infection. Listeria infection can result in miscarriages, premature delivery, and stillbirths. Pregnant women can transmit the infection to their unborn babies. The infection can cause serious illness and even death in newborns.

More than half of all listeriosis cases occur in people 65 and older, because the immune system and organs of older people are not as capable of recognizing and ridding the body of harmful germs, such as those that trigger food poisoning. Because older adults may also have chronic conditions, including diabetes and cancer, they may have weakened immune systems due to prescribed medications. There is also a reduction in stomach acid when people age, making it harder to kill germs and reduce the risk of illness. Thus, adults 65 years and older are 4 times more likely than the general population in the United States to get Listeria infections.

People whose immune systems are compromised due to medical conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, liver or kidney disease, alcoholism, and HIV or AIDS, are susceptible to listeriosis. Treatments that interfere with the body’s ability to fend off illness, such as steroids and chemotherapy, also increase the odds of contracting a Listeria infection. Some medical conditions and treatments can weaken the immune system and enable the body to react more intensely to contaminated food.

What Is Listeria?

As explained by Larry M. Bush, MD, in Merck Manuals, most listeriosis cases are the result of eating contaminated food, such as raw food and uncooked meat, that has been improperly cooked or handled. Listeria bacteria sneak in through the bloodstream and go on a rampage, spreading to other organs. The bacteria have also been known to infect the skin of people who have direct contact with infected animals, like veterinarians, farmers, and slaughterhouse workers. A hardy germ that can even grow on refrigerated foods, Listeria can go unnoticed in the equipment or appliances where food is prepared, including in factories and grocery stores.

Listeria bacteria can contaminate food at refrigerator temperatures and even stay alive in the freezer. Pasteurizing dairy products can help kill Listeria, as can proper cooking or reheating of food. Keep in mind that Listeria bacteria are survivors and can thrive in cracks filled with food and untouched and inaccessible areas in commercial food preparation facilities where food is not adequately prepared or stored. When food needs no further cooking when bought, remaining bacteria are eaten with the food.

Listeria can grow in refrigerated, packaged, ready-to-eat products without altering the taste or smell of the food. Foods often implicated in listeriosis outbreaks are soft cheeses, delicatessen salads, unpasteurized milk, cold cuts, hot dogs, seafood, raw meat, and undercooked chicken.

Symptoms of Listeriosis

Listeriosis can manifest with myriad symptoms according to the individual and part of the body affected. Like other foodborne illnesses, listeriosis can show up as fever and diarrhea, but these instances are rarely diagnosed, with symptoms lasting for 1 to 7 days.

The symptoms of Listeria infection normally begin 1 to 4 weeks after eating contaminated food. Some people might have these symptoms as long as 70 days after exposure, while others may experience them as early as the day of exposure.

Symptoms of invasive listeriosis, when the infection spreads beyond the gastric organs, manifest differently in pregnant and non-pregnant individuals. Although pregnant women usually have only fever and other flu-like symptoms, such as fatigue and muscle aches, a Listeria infection while carrying can result in miscarriage, stillbirth, early delivery, or life-threatening infection of the newborn. People who are not pregnant may have such symptoms as headache, confusion, loss of balance, a stiff neck, convulsions, fever, and muscle aches.

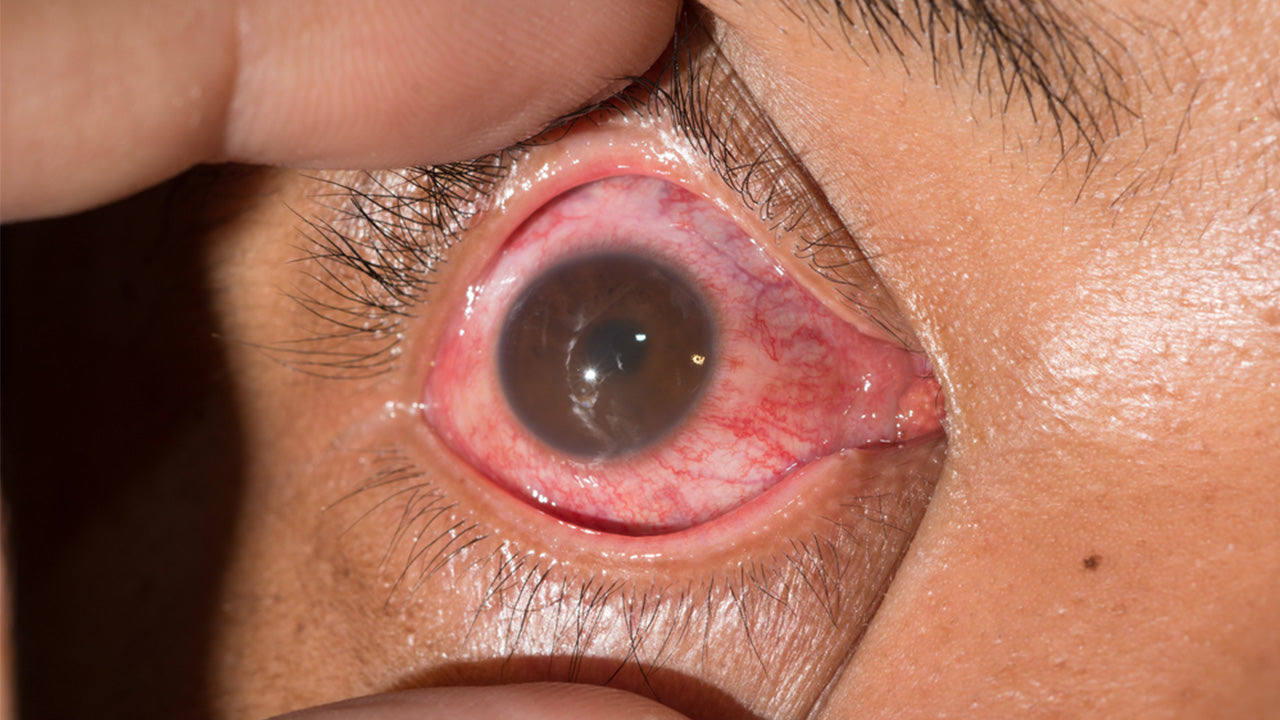

Invasive listeriosis involves the bacteria entering the bloodstream from the intestine and invading other organs. Bacteria may spread to the nervous system and tissues covering the brain and spinal cord (causing meningitis); eyes; heart valves (causing endocarditis); joints; and, in the case of pregnant women, the uterus and fetus. Infrequently, there can be collections of pus (abscesses) in the brain and spinal cord.

Listeriosis Diagnosis

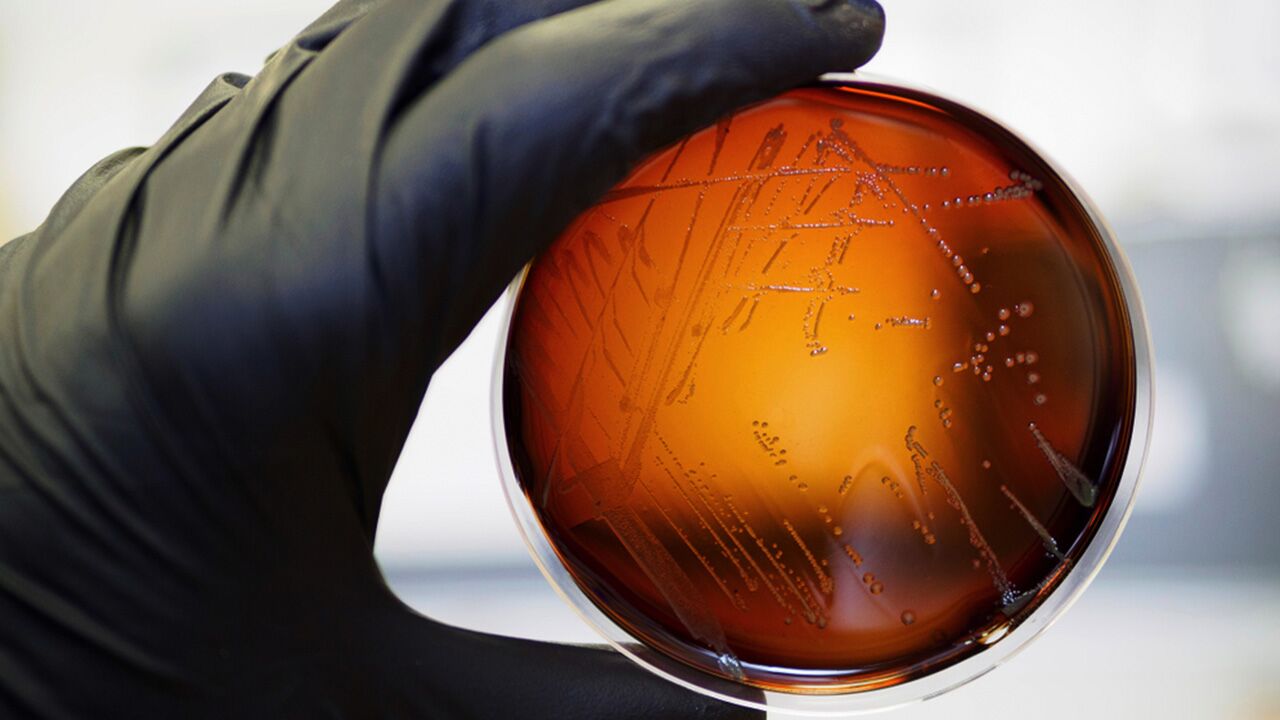

To diagnose listeriosis, doctors take a blood sample. If symptoms of meningitis are present, doctors will do a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) to obtain a sample of the cerebrospinal fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord. After culturing, the bacteria are identified to confirm the diagnosis. In most cases, Listeriosis can be diagnosed when a bacterial culture is used to grow Listeria monocytogenes from a body tissue or fluid, such as blood, spinal fluid, or the placenta.

Listeriosis Treatment

Most people with Listeria infections spontaneously recover from the infection in about one week. Patients in high-risk groups, particularly pregnant women in the third trimester, usually need immediate intravenous antibiotics to stop or retard the progress before it becomes a more invasive disease. Treatment with antibiotics early on can save the life of the fetus.

The antibiotics ampicillin and gentamicin are administered intravenously to most people with listeriosis, including endocarditis and meningitis. People who are allergic to penicillin medications receive medications such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Physicians treat listeriosis-related eye infections with erythromycin, given orally, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, given intravenously.

The course of antibiotic treatment depends on how severe the infection is. A patient with meningitis typically receives treatment for 3 weeks, while patients with brain abscesses undergo antibiotic treatment for 6 weeks. IV ampicillin is the go-to treatment for listeriosis. Bactrim (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) is another successful medication. Researchers say that every patient’s treatment ought to be customized for best results. If diagnosed with a Listeria infection, your health care team should include an infectious-disease consultant, and if pregnant, an obstetrician and a pediatric specialist.

Listeria Contamination Prevention

The CDC recommends following the safe purchasing and preparation guidelines at www.FoodSafety.gov, the federal gateway for food safety information.

In the 1990s most outbreaks involved deli meats and hot dogs. Currently, dairy products and produce are implicated in Listeria outbreaks. Recent outbreaks have been traced to soft cheeses, cantaloupe, celery, sprouts, and ice cream.

Listeria bacteria can reproduce at refrigerator temperatures, meaning that food lightly contaminated can become heavily contaminated while in the refrigerator. It is important to take precautions, especially for people at risk of serious consequences if infected. These people should not eat:

- Soft cheeses made from unpasteurized milk (including feta, Brie, Mexican-style cheeses like queso fresco and queso blanco, and Camembert)

- Refrigerated ready-to-eat foods (including luncheon meats, hot dogs, pȃtés, and meat spreads), unless heated to an internal temperature of 165 °F (73.9 °C ) or until steaming hot just before serving

- Refrigerated smoked seafood (including foods labeled nova-style, lox, kippered, smoked, or jerky), unless cooked

- Raw (unpasteurized) milk and cheeses made from raw milk

In addition to washing raw vegetables and fruits before consumption, always wash hands and all kitchen surfaces, appliances, utensils, and cutting boards after use. Apart from sanitation, there are many ways to reduce the risk of infection.

- Refrigerate leftovers within two hours in shallow, covered containers and use them within three to four days.

- Set the refrigerator temperature at 40 °F (44.4 °C) or lower.

- Set the freezer at 0 °F (-17.8 °C) or lower.

Listeriosis prevention is a matter of being very cautious with food selection, preparation, and storage and understanding food poisoning risks. The safe food guidelines—Clean, Separate, Cook, Chill—at www.FoodSafety.gov are some helpful best practices to follow.

The CDC says Listeria effects may not arise for several weeks, at which point it’s increasingly difficult to figure out the contaminated food source. The bacterium can contaminate many foods that don’t require cooking, such as cheese, as well as foods unlikely to be affected, including fruits and vegetables like celery and cantaloupe. It is also helpful to keep your immune system strong with nutritional aids like essential amino acids.

The CDC recommends the following prevention techniques:

- Using special laboratory tests and disease detectives to help quickly identify outbreaks.

- Finding and removing contaminated food before consumption.

- Learning from past outbreaks and conducting environmental investigations to make food safer.

- Implementing new safety measures for food production, such as those included in the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), to reduce food contamination.

- Diligently following USDA guidelines to help reduce instances of Listeria contamination of ready-to-eat meat and poultry products.

- Working at developing a strong and effective public health system that offers the tools and resources necessary to champion food safety.

- Investigating and creating the most effective policies and practices.

Up to 25% off Amino

Shop NowTAGS: conditions

Join the Community

Comments (0)

Most Craveable Recipes

833-264-6620

833-264-6620