What’s with HMB Supplements?

By: by Amino Science

By: by Amino Science

From hydroxymethylbutyrate to beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (or β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate), HMB—a chemical produced when the body breaks down the amino acid leucine—is known by a variety of names. But what exactly are HMB supplements?

HMB supplements are promoted as nutritional substances that can help speed wound healing and support individuals with muscle-wasting diseases such as cancer and HIV. Proponents also tout HMB supplements (or HMB in combination with creatine monohydrate) as a way to slow the muscle wasting that comes with aging.

To be fair, research does support the presence of some beneficial effects of HMB. For example, it’s been shown to promote muscle growth in individuals who work out. However, it should also be noted that this muscle-promoting effect is dependent on the adequate availability of essential amino acids (EAAs).

In other words, HMB supplements in isolation, without the support of EAAs, have a minimal effect on muscle building.

How Does HMB Work?

HMB and the EAA leucine are closely linked, and it’s necessary to understand the relationship between them to understand how HMB works.

Leucine is the most abundant of the nine EAAs found in muscle protein. It also acts as a nutraceutical aid in turning on the body’s muscle-building switch. In fact, it’s one of the three branched-chain amino acids—the others being isoleucine and valine—that make up about a third of muscle protein. Some experts also propose that leucine turns on the process of protein synthesis (muscle building) via the action of HMB.

HMB is a metabolite of leucine, meaning it’s derived from the breakdown of leucine. In a series of step-by-step reactions, about 15% of the leucine present in blood is also irreversibly broken down to ammonia and carbon dioxide. This sequence of reactions by which leucine is reduced to its basic components is called a metabolic pathway.

But there’s more than one metabolic pathway involved in the breakdown of leucine. And it’s actually via a minor pathway that the leucine metabolite HMB is produced, yet it’s still proposed to be the active component of leucine. However, as leucine is being broken down by the body, only about 5% of it is broken down via the pathway that results in HMB.

Combine this with the fact that only 15% of leucine is broken down at any given time, and it’s clear that the amount of HMB produced by leucine breakdown makes up only a very small percentage of available leucine.

As a result, the concentration of HMB in body fluids is far less than that of leucine. And since results with dietary supplementation aren’t achieved unless the concentration of HMB is increased many times above the normal physiological level, it’s unlikely that leucine’s effects on muscle protein synthesis are, in fact, mediated by HMB.

However, when the availability of HMB is increased using dietary supplements, it seems to work as a nutraceutical in the same way leucine does in that it activates the molecular mechanisms involved in the initiation of protein synthesis.

Specifically, the increase in HMB concentration supplied by supplementation activates a molecule known as mammalian target of rapamycin, or mTOR.

The molecule mTOR plays a key role in controlling the initiation of protein synthesis. When mTOR is activated, a series of additional chemicals involved in the initiation of protein synthesis is activated as well. And when all of these molecules are switched on, the process of protein synthesis begins. Likewise, when mTOR is activated by excess levels of HMB, the process of protein synthesis is also stimulated.

A sustained increase in muscle protein synthesis should ultimately be reflected by an increase in muscle strength, function, and mass over time. However, the use of HMB alone does not result in an increase in protein synthesis.

In fact, any increase in protein synthesis resulting from HMB supplements will last only as long as there’s an adequate supply of EAAs. And once there’s a dip in the EAA supply, the effect of HMB stops as well.

HMB Needs EAAs to Work

If you activate mTOR but your body doesn’t have enough EAAs circulating in the bloodstream, then muscle protein synthesis will only be increased to a limited extent.

As stated earlier, muscle protein contains nine EAAs, each of them unique and each a vital component of newly produced proteins. Unlike the 11 nonessential amino acids, EAAs can’t be produced in the body and have to be obtained through dietary sources.

However, if you aren’t getting enough EAAs through protein-rich foods or EAA supplements, then your only source of EAAs is the protein already present in your body.

In this case, your body begins to break down its protein stores and release the component amino acids, including EAAs, for use by the cells of the body. However, under normal conditions, only about 85% of amino acids released in this manner are reincorporated into protein; the rest are lost to oxidation.

But let’s circle back to HMB.

To be effective on its own, HMB must increase the efficiency of EAA reutilization for protein synthesis. However, as we just indicated, that process is already 85% efficient, which means there’s a definite limit as to how much more efficient the recycling of EAAs back into protein can be.

Therefore, it becomes clear that dietary supplementation with HMB works only when there’s an excess amount of EAAs available. And an excess supply of EAAs can occur via only two mechanisms:

- EAAs must be consumed at the same time as HMB

- The rate of protein breakdown must be accelerated

However, an increase in protein breakdown would only undermine the beneficial effect of an increase in protein synthesis, as protein gain is the result of the balance between protein synthesis and breakdown. Thus, supplemental doses of HMB can only result in a sustained increase in the net gain of muscle protein if consumed at the same time as an abundant supply of EAAs.

Benefits of HMB Supplements

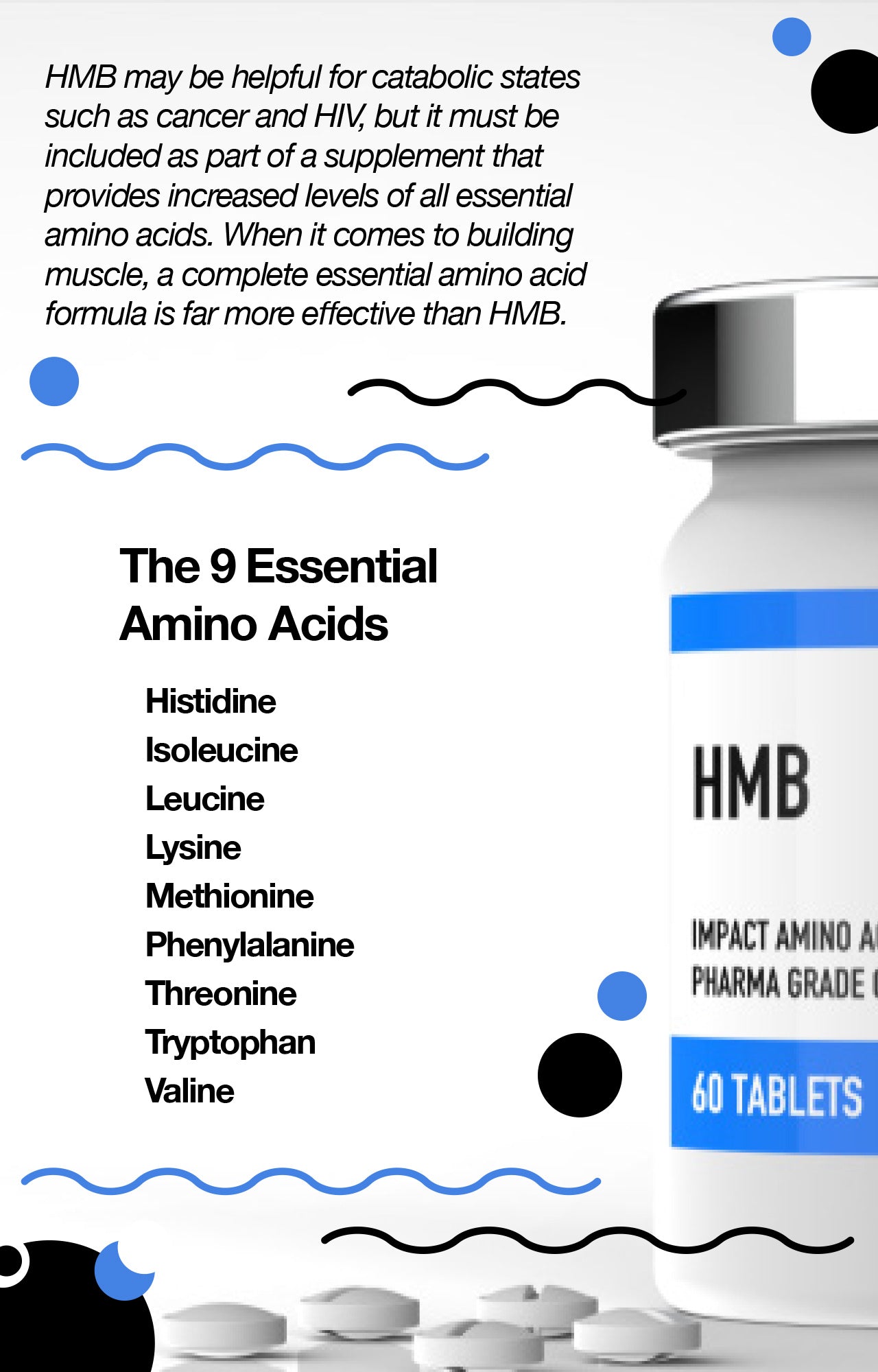

All this being said, there are still a few conditions—such as catabolic states involving rapid muscle loss—that may benefit from HMB supplementation. This is because protein breaks down much more rapidly in catabolic states such as critical illness or HIV.

This protein breakdown provides extra EAAs that would, under normal conditions, be oxidized. In these situations of increased EAA availability that occur during catabolic states, the anti-catabolic action of HMB may help maintain muscle mass and function and decrease the rate of muscle protein breakdown.

However, recommendations for catabolic states generally specify that HMB should be included as part of a multifaceted approach for muscle maintenance that also incorporates resistance training and a high-protein diet for EAA maintenance.

Exercise also accelerates muscle breakdown (via muscle damage that occurs as a natural part of muscle use) and EAA oxidation. Consequently, the use of supplemental HMB may result in improved performance by improving the reutilization of EAAs released by protein breakdown for the synthesis of new protein.

Is HMB Better Than EAAs Featuring Leucine?

The body’s response to dietary supplementation with HMB alone is similar to that resulting from supplementation with leucine alone.

Just as HMB requires the presence of elevated levels of all the EAAs, so, too, does leucine require the other EAAs to be effective. In addition, the body’s response is more robust when leucine is included as part of a mixture of all the other EAAs than when it (or HMB) is used alone.

Two studies performed in the same laboratory, using the exact same protocol, demonstrate this most clearly. In one experiment, the effectiveness of HMB was assessed, and in the other experiment, the effectiveness of a mixture of EAAs (containing about 40% leucine) was determined.

Both studies investigated how effective HMB and EAA supplements were, compared with a placebo, at diminishing the loss in muscle mass and function that normally occurs with inactivity.

The subjects tested were over the age of 65, and both lean body mass and performance on various physical function tests were measured before and after 10 days of strict bed rest.

In the first study, following 10 days of bed rest, participants were put through a strength training program for a period of 8 weeks. In addition, beginning 5 days prior to bed rest and lasting until the end of the rehabilitation phase, the control group received a placebo powder and the subjects in the experimental group received 1.5 grams of HMB twice daily in its calcium salt form, for a total of 10 weeks of supplementation.

In the second study, participants in the control group received a placebo, while subjects in the experimental group received 15 grams of EAAs 3 times a day throughout the entire 10 days of bed rest. However, in this study, neither group received any weight training.

When comparing the data collected on all the subjects included in these studies, it becomes clear that the major differences between HMB and EAAs can be seen in terms of the tests of physical function—all of which have been validated as representative of the normal physical requirements for activities of daily living in older adults.

While the placebo group had major impairments in all tests of physical function after 10 days of bed rest, those given EAA supplementation—but not HMB supplementation—had significantly improved outcomes.

For example, the time required for subjects to go from a standing position to the floor and back up again (floor transfer test) increased by approximately 40% in the placebo group. Floor transfer rate was also not significantly affected by HMB supplementation. However, the group given EAA supplementation shortened their floor transfer time by 6%.

In another example, the time required to walk up a flight of stairs increased by 18% in the placebo group. HMB once again had no beneficial effect on this response, but those receiving EAA supplementation showed virtually no increase in the amount of time it took them to perform this task.

Finally, the number of toe raises (test of foot flexibility) that could be completed in 1 minute was reduced by almost 80% in both the control group and the HMB supplementation group, whereas the loss of this function with bed rest was completely prevented with EAA supplementation.

These bed rest studies are the only direct comparison that’s been completed of the muscle-building effects and strength gains provided by dietary supplementation with HMB and a formulation of EAAs. Yet the results clearly demonstrate the beneficial effects of EAAs in preventing declines in physical function and fail to demonstrate any beneficial effect of HMB alone.

These results are also consistent with the fact that stimulation of protein synthesis requires the availability of excess amounts of all component amino acids—especially EAAs.

While HMB’s activation of mTOR and other molecules involved in the initiation of protein synthesis may result in a transient increase in muscle protein synthesis, this increase can’t be sustained at a rate sufficient to result in improvements in physical function.

The HMB Takeaway

HMB is widely promoted as a muscle-building molecule that stimulates protein synthesis. While in some cases HMB supplementation may provide benefits, direct comparison with EAA supplementation highlights the fact that any benefit provided by HMB is minimal.

Whatever molecular signaling occurs as a result of HMB supplementation can instead be achieved by taking an EAA supplement that contains leucine. The availability of all EAAs—which are not present in HMB supplements—in excess amounts is required for a sustained increase in protein synthesis, muscle cell growth, and body composition changes that result in greater lean mass versus fat mass.

Furthermore, combining HMB with EAAs would not be expected to be particularly helpful, as the EAAs would elicit the action of HMB on their own.

Up to 25% off Amino

Shop NowTAGS: supplements

Join the Community

Comments (0)

Most Craveable Recipes

833-264-6620

833-264-6620