Creatine: What It Is, What It Does and the Best Way to Benefit

By: by Amino Science

By: by Amino Science

The amino acid creatine was first discovered in 1832, when the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul extracted the compound from meat. However, over 150 years passed before the public paid any attention.

It wasn't until the 1992 Barcelona Olympics that creatine finally rose to notoriety, when the performance of several British athletes so exceeded expectations that it was later revealed they’d incorporated creatine supplementation into their nutrition regimen.

Since then, interest in this amino acid has only grown, with creatine now being reported as the most widely used performance-enhancing compound by both amateur and professional athletes.

In fact, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Americans consume almost 9 million pounds of creatine each year.

What Is Creatine?

Creatine is a nitrogenous compound synthesized from the amino acids glycine, arginine, and methionine. While it's considered technically an amino acid as well, creatine isn’t one of the 20 amino acids used to build the proteins in our bodies. Rather, it helps support energy metabolism in the muscles.

Because of this, creatine is probably the most researched dietary supplement in the world, with more than 500 papers already published examining the effects of supplemental creatine, especially on exercise performance. And, indeed, the large majority of these studies have shown beneficial effects of creatine on athletic performance.

Where Does Creatine Come From?

As stated earlier, creatine is produced in the body, but we can also obtain the amino acid from the foods we eat, especially meat and fish. People who have low levels of creatine in their diet, particularly vegetarians, seem to benefit the most from creatine supplementation.

How Does Creatine Help Exercise Performance?

Creatine supplementation actually performs two important functions for the muscles of the body.

- It provides the extra energy needed for high-intensity, short-duration exercise.

- It delivers that energy where it's needed most.

Energy for High-Intensity Exercise

Creatine is converted to phosphocreatine, or creatine phosphate (CP), in the muscles. CP serves as a source of energy for explosive exertion, such as that found in sprinting and weight training.

In addition, the muscles of the body are powered by adenosine triphosphate (ATP)—the major form of chemical energy needed for muscle contractions. However, muscles run through their supply of ATP very quickly, and something extra is necessary to help regenerate it.

This is where CP plays a role. CP is broken down by the muscles to provide the extra energy you need when you’re using more ATP than you’re regenerating in your mitochondria—the energy factories of the cell.

It’s this extra supply of energy (although quickly used up) provided as CP that's credited with producing greater gains in muscle mass and strength from resistance training and improving performance in the high-intensity activities of athletes such as weight lifters and sprinters.

Energy Where It’s Needed Most

While it’s long been recognized that supplementing with creatine can increase the amount of CP in muscle—thereby improving athletic performance in areas that require more rapid use of energy than can be supplied by ATP production alone—the “energy carrier” role of the creatine-phosphocreatine system is less well appreciated.

Without the creatine-CP system, ATP would be unavailable to the contracting muscles because it’s this pathway that provides the cellular energy transport through which ATP moves from the mitochondria to the muscle cell site that needs it.

Benefits of Creatine Supplementation in Athletes

As mentioned earlier, creatine supplements are widely used by athletes, and the use of creatine has been shown to benefit those engaged in high-intensity, short-duration exercise.

Benefits of creatine for athletes may include:

- Increased skeletal muscle mass

- Increased muscle contraction speed

- Increased strength

- Improved muscle recovery

- Enhanced fatigue resistance

However, the extent of the beneficial effect offered by creatine supplementation depends on how much is consumed in the normal diet and the athlete’s chosen sport.

For example, studies have shown that the benefits of creatine begin to wane after approximately 90 to 150 seconds. Therefore, athletes involved in endurance exercises such as long distance running wouldn’t achieve the same benefit with creatine supplements.

However, a recent study did show that creatine has the ability to raise the lactate threshold (the point at which lactic acid begins to accumulate faster than it can be removed), which would result in endurance athletes being able to exercise longer without fatiguing.

In athletes, the beneficial long-term effects of creatine, such as improvements to body composition based on increased lean body mass, are generally attributed to enhanced training capacity. For instance, creatine supplementation may enable you to lift heavier weights, which in turn would help your muscles grow larger.

But what about older adults? Would creatine supplements help them too?

Benefits of Creatine Supplementation in Older Adults

The process of aging is associated with decreased muscle mass, strength, and function. And as we grow older, our ability to perform resistance exercise or high-intensity training often decreases.

However, a review of the literature indicates that creatine supplementation—even without resistance training—seems to enhance muscle creatine stores, muscle mass, strength, and function in older adults. Creatine has been found to increase bone mineral density in this population as well.

Other studies have also demonstrated the beneficial effects of creatine on neurological function in both younger and older adults.

Because of positive results in animal studies, there was initially great interest in the possible benefits of creatine supplementation in Parkinson's disease. However, a recent meta-analysis did not find evidence to support its use, though more studies were recommended.

Adverse Effects of Creatine Supplementation

According to the Mayo Clinic, supplemental oral creatine is generally considered safe for a period of up to 5 years. However, there is some evidence that the use of creatine in high doses may cause heart, liver, or kidney damage.

Other potential side effects include:

- Water retention

- Dehydration

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Weight gain

- Muscle cramps

How to Supplement with Creatine

If you've decided you're ready to add supplemental creatine to your diet, you need to know what forms are out there and when and how much you should take.

What Forms of Creatine Are Available?

Creatine is available in an almost bewildering array of forms. These include:

- Creatine monohydrate

- Creatine citrate

- Creatine malate

- Creatine ethyl ester

- Creatine magnesium chelate

- Creatine pyruvate

However, the best known and most studied form is by far creatine monohydrate. It’s also inexpensive and generally well tolerated by most individuals.

When Should You Take Creatine?

While creatine itself is not used for energy during exercise—unlike glycogen, your muscles’ primary source of fuel—as noted earlier, it does serve to transport energy in the mitochondria to contracting muscles.

Therefore, in theory, it shouldn’t matter whether you take it before your workout or after, especially when you consider its potential beneficial effect even without exercise.

A recent paper supports the notion that it’s preferable to take creatine—in the form of creatine monohydrate—after a workout. However, further inspection of the data the researchers used reveals that taking creatine after a workout really doesn’t make that much difference.

Other researchers have argued that the beneficial effect of creatine supplementation is more pronounced with pre-workout consumption, and still others maintain it doesn’t really make any difference.

The bottom line is that if there’s still a lot of debate on the best time to take creatine, the fact that you actually take it probably matters more than when you take it.

How Much Creatine Should You Take?

Taking as many as 20 grams of creatine powder or liquid a day for 5 days and as many as 5 grams a day thereafter is often recommended for optimal support of athletic performance.

However, doses at high levels such as these can cause undesirable side effects, including muscle cramping, nausea, diarrhea, gastrointestinal pain, and dehydration.

It’s also likely that much smaller doses can help promote muscle growth and improved muscle function over time.

Unless you’re vegetarian or vegan, the typical daily dietary intake of creatine is about 1 gram, which is the same amount that’s produced in the body each day.

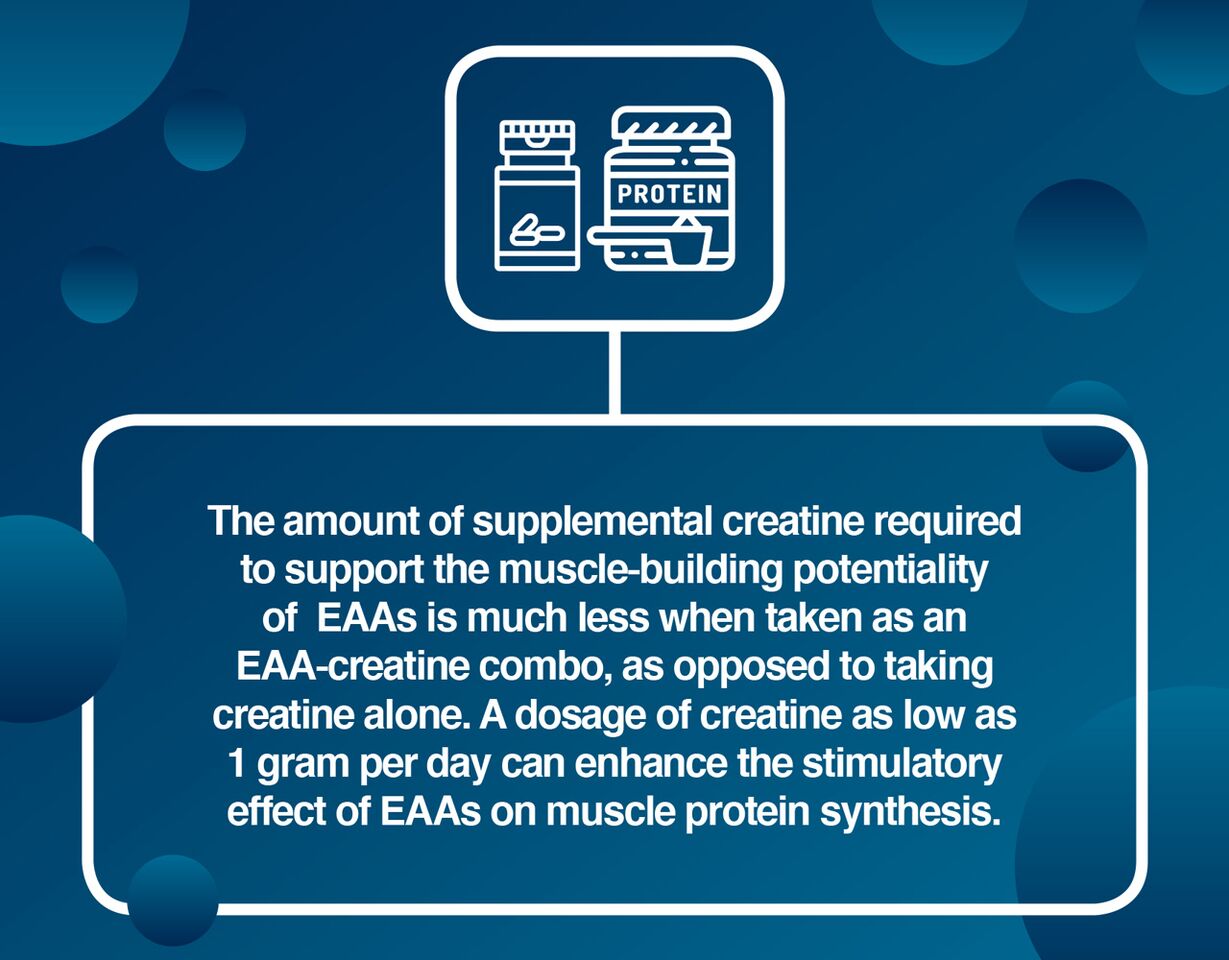

Therefore, a 1-gram dose of creatine would be approximately double the amount of creatine you get on a daily basis from your diet. This increase should be adequate to promote enhanced muscle protein synthesis—if supplemental essential amino acids (EAAs) are provided at the same time.

Why You Need Additional Amino Acids with Creatine

Whether you’re an athlete looking to maximize performance and muscle gain or simply moving into your golden years and seeking to increase or maintain muscle strength as you age, your success rests on muscle protein synthesis.

This is because the muscle-building process is dependent on the activation of muscle protein synthesis to increase muscle mass and strength—even in the absence of exercise. And muscle protein synthesis requires energy in the form of ATP as well as amino acids to help build muscle proteins.

While creatine alone can provide extra energy for muscle protein synthesis, without increased availability of all EAAs, only a limited amount of new muscle can be produced.

This is why results from creatine supplementation can be variable. If adequate amounts of EAAs aren’t available, there can be only minimal stimulation of muscle protein synthesis.

What do we mean by this?

As stated earlier, there are 20 different amino acids that make up the proteins responsible for the construction of muscle fibers. And nine of these—the essential amino acids—are not produced in the body. For new muscle protein to be created, all the EAAs are needed in proportions specific to the composition of each particular protein.

An EAA supplement is a powerful stimulus of muscle protein synthesis, but the amount of protein produced will ultimately be limited by how much energy (in the form of ATP) is ready to go at the site of muscle protein production. And this is where creatine comes in.

Creatine provides the necessary energy to support an increased rate of muscle protein synthesis. And, consequently, there’s an interactive effect between EAA availability and the amount of creatine in muscles.

In other words, while creatine supplementation alone can’t produce new muscle protein, the presence of extra creatine can enhance the stimulatory effect of supplemental EAAs by providing the additional energy needed for the production of new protein.

For those interested in all the benefits creatine has to offer, this is indeed a winning combination. Click here for a clinically proven and patented EAA + creatine supplement that can increase your performance gains 4-fold.

Up to 25% off Amino

Shop NowTAGS: supplements

Join the Community

Comments (0)

Most Craveable Recipes

833-264-6620

833-264-6620